It was shortly after noon in the quiet town of Milbrook when a blow at the door of Dr. Ethel Glenfield’s consultation changed the course of his career, and possibly of the entire registered history of the town. Dr. Glenfield, a veteran historian known for her deep knowledge of prebélica America, was drinking tea with her colleague, Dr. Alaric Featherstone, when a young messenger handed her a brown package without sender.

History books

What seemed like a normal shipment soon became one of the most shocking and significant discoveries in early history of the United States.

“Who sent this?” Ethel asked, narrowing his eyes. The messenger simply shrugged. Dentro del paquete había un solo objeto: un daguerrotipo reluciente —una rara fotografía temprana de mediados del siglo XIX— cuya placa de plata pulida estaba increíblemente bien conservada. Junto a él, una breve nota: “De los archivos de la Sociedad Histórica de Milbrook. Por favor, examínelo cuidadosamente. Instalaciones de la Casa Clifton”.

Dr. Featherstone approached, curious. “Clifton? How the Clifton family of the former Quacker Settlement?”

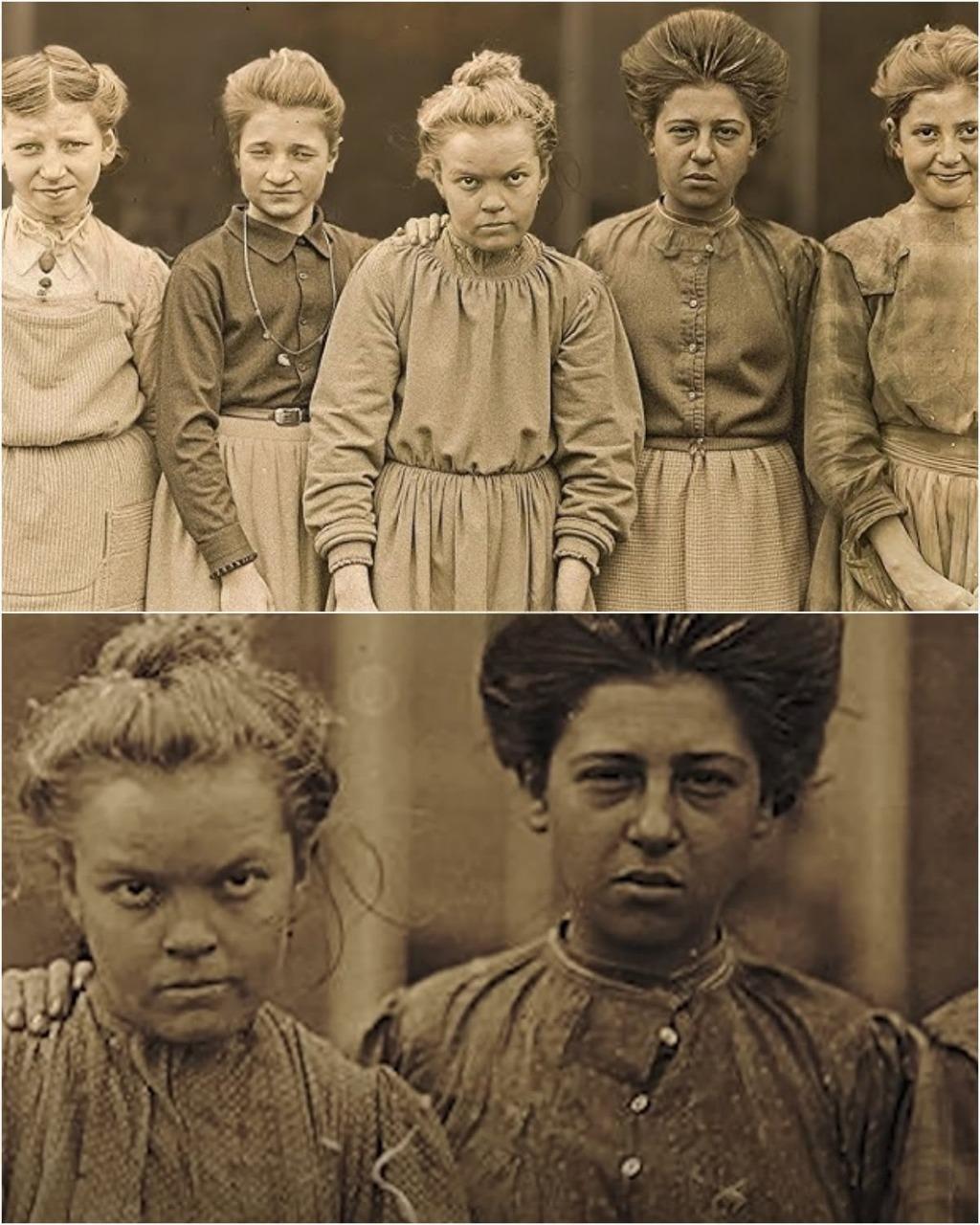

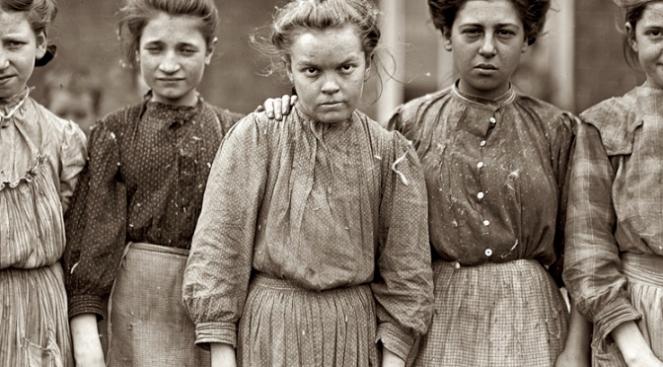

Ethel nodded, already taking out a magnifying glass from his drawer. Photography, although discolored by time, was amazingly detailed. Five girls were standing in a rigid row, with their worn but clean dresses, their penetrating looks.

The photo that was not silent

At first glance, it seemed simple: five sisters, presumably between ten and sixteen, posed in front of a worn wooden structure. But when examining the panel, the two historians noticed something unusual: the expressions of the girls were not rigid or formal, but rather marked by something deeper: tiredness, determination and silent sadness.

The left -wing girl wore her brown hair on wild braids and smiled slightly. The two of the middle, presumably twin judging by their features, were standing with tense shoulders and looks at the front. But it was the last girl, the end of the end, who made Ethel stop. His skin tone was remarkably darker than that of the others, and his hair was collected in a disheveled bun. He smiled openly, radiating hope and innocence. The message was immediately palpable: this family was integrated, something unheard of in the United States of the 1830s.

“They are sisters,” said Featherstone finally, just in a whisper. “But not all are blood relatives. Notice how they stay: protectors, as if they had already fought battles that most people never see.”

Forgotten records, hidden names and the bond of 1836

Civil War Artifacts

Promoted by a sudden urgency, Ethel brought the family registration of his people from the shelf. It was a dusty book, bound in leather, which had consulted countless times, but never for this occasion. After leafing through dozens of fragile pages, it was decided by a family name: Clifton, Edna, Lucy, Mabel, Kate, Rose.

Born between 1830 and 1833. All were daughters of Elijah and Harriet Clifton. Edna, Lucy and Mabel were biological sisters. Kate and Rose, adopted. Rose, the youngest, was the daughter of a liberated slave. An entry into the records said: “Adopted by a Quaquera family after the death of her mother in childbirth.”

Together, they formed one of the most progressive homes in the region: local activists, music and philanthropists known to help fugitive slaves and take care of orphans. But the situation worsened in 1847. That year, the whole family died in a fire.

A more detailed analysis reveals an even darker secret.

The surface of the daguerreotype shone under the light of the window. Ethel narrowed his eyes and returned to his magnifying glass. Then he noticed something in the background: not only a landscape, but people. Children. At least a dozen, perhaps more, partially blurred, but clearly visible. Dresses with simplicity, with reserved expressions.

“They are not just posing,” he said slowly. “They are standing in front of something.”

Ethel expanded the image on its monitor, complemented with a high resolution scan that had just completed. The children had no kinship. They had different skin color, height and facial features. And most importantly, they were not there by chance. His clothes was made. They were standing in ordered rows.

Recorded near the corner of the photograph there was such a faint inscription that it was almost impossible to ignore it: 8: 15: 1836.

Civil War Artifacts

“August 15, 1836,” Featherstone read aloud. That was more than a year before the fire of the house.

Ethel’s hands trembled as he rushed among the archived newspapers. A brief article of the same week finally provided context: “A local family houses 14 children rescued from an illegal nursery.” The details remain secret to the trial. The family? The Clifton.

The truth opened like a pestillo hidden after centuries: this photograph was not just a portrait, it was a test. It was a visual record of the consequences of one of the first known rescues of children from the era of trafficking in the history of the United States.

Civil War Artifacts

Why the photo was commissioned and hidden

Milbrook’s judicial records revealed that the daguerreotype was created at the request of the Quaquera community to serve as documentation for the subsequent trial of the rescue. Fourteen children were found in a hidden basement under a nearby warehouse, hungry, battered and waiting to be transferred to the south. The Clifton discovered the place following a letter in the underground railway.

Rose, with just ten years, comforted the youngest children for three days before the authorities arrived. Mabel and Lucy attended the wounds. Edna spoke with the judge.

The trial was controversial and received little advertising. Three men were convicted and others released. Weeks later, the Clifton’s house fell completely, an act officially classified as “accident”, but that it was suspected for a long time that it was a fire caused.

A legacy written in ashes

The two historians were silent, overwhelmed by the seriousness of their discoveries. “They were killed,” said Featherstone. “Because they told the truth.”

Ethel nodded with the broken voice. “And now, almost 200 years later, we can finally tell your story.”

The image was subsequently part of an emblematic exhibition of the Milbrook historical society entitled “The Clifton sisters: unknown heroines of the underground railroad.” In a quiet corner of the exhibition, a plaque counted the names of the five girls, along with those of the fourteen boys they had saved.

A visitor later described the moment: “I stayed there, looking into the eyes of five young people who knew what was right and decided to act. I realized: sometimes the courage does not look like a battlefield. Sometimes it looks like five teenagers with hand -sewn dresses, trapped between evil and innocence.”

Final reflections: a story that needs to be known

This was not just a fragment of photographic history; It was the key to a forgotten legacy of justice, compassion and deep courage. The Clifton sisters were more than simple kind girls of a progressive home. They were pioneers in child protection and social justice, decades advanced to their time.

And the photo? I was no longer forgotten, buried in a file. Now he gave testimony of a truth that generations had overlooked and that the world would never forget.

What would you have done instead? Would you risk your life to protect those who have no voice?

Tell us in the comments and share this story if it moved you. That the story remember not only the photo, but also the purpose that motivated it.