In 1718, Fredriksten Fortress’s battlefield in Norway became the stage of one of the most durable mysteries in history: the death of the Swedish king Charles XII, a warrior whose relentless ambition restructured the great war in northern Europe. Beef by a projectile through his skull while inspecting his troops, Charles instantly fell, his death as bold and dramatic as his life. Was it a street bullet of the Norwegian enemy, or a traitor inside his own ranks took advantage of the moment? More than 300 years later, the question persists, fed by witnesses and witnesses, a strange trajectory of the wound and a 1917 chilling autopsy that offered more questions than answers. With Tiktok detectives and historians still buzzing, this story of the disappearance of a king captivates us with his combination of war, betrayal and forensic intrigue.

1. The final position of the warrior: the siege of Fredriksten, 1718

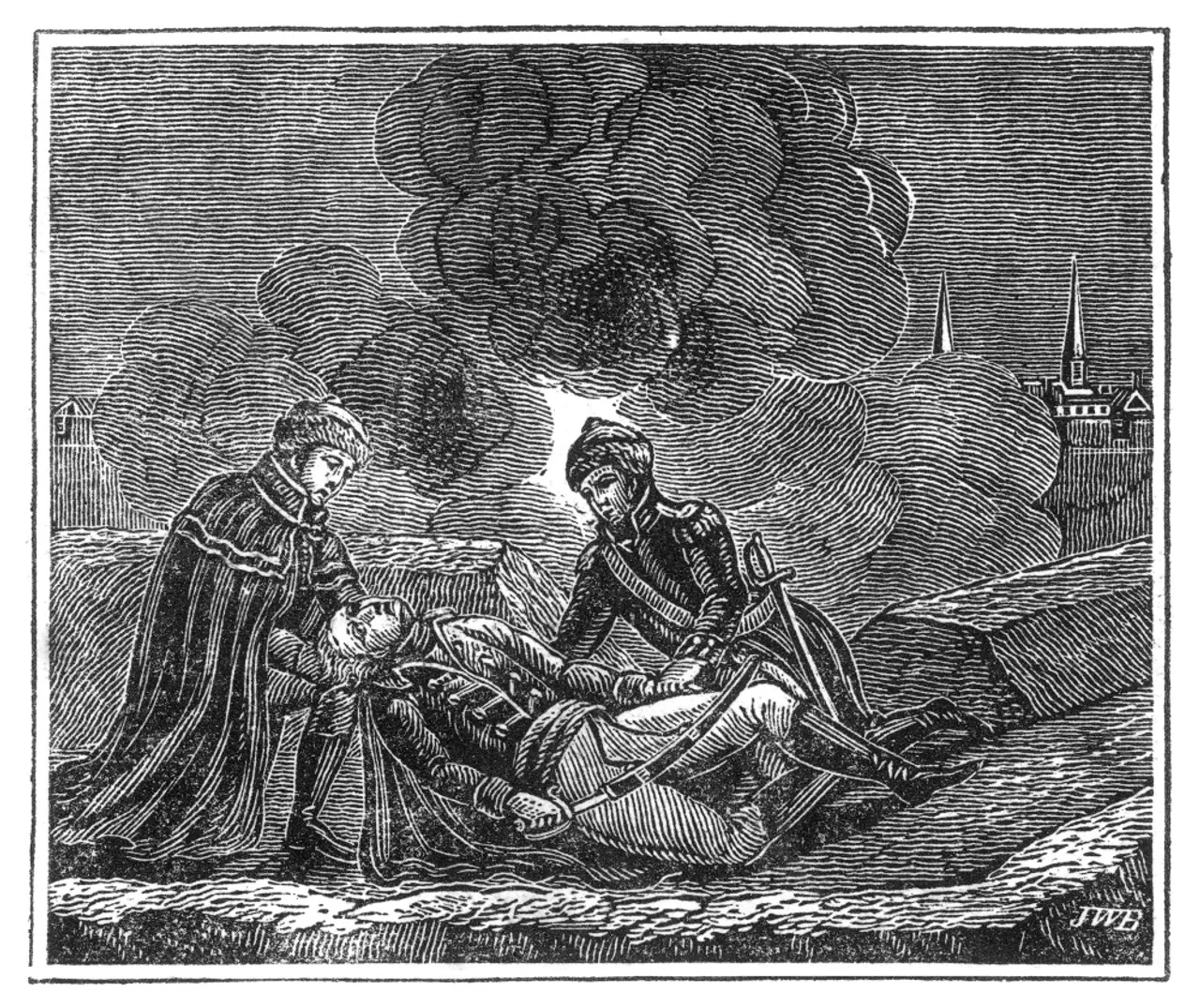

Charles XII, called “The North Lion”, was a bigger figure than life whose military genius and boldness defined the role of Sweden in the Great North War (1700-1721). By 1718, at 36, he had directed daring campaigns against Denmark, Poland and Russia, winning a courage of courage, often joining the first -line battles with its blue and yellow uniform. The siege of Fredriksten, a Norwegian fortress held by Denmark-Norway, was his latest commitment to claim lost territories. On November 30, 1718, under Night, Charles went up to the walls to inspect the trenches of his troops. Around 9 p.m., a projectile, probably a musket ball or a grape, hit the left side of its skull, leaving the right. He died instantly, his body fell into the mud, finishing a 21 -year -old reign.

The scene was chaotic: Swedish soldiers, stunned, carried their king’s body back to the camp, while the siege hesitated (Fredriksten was retained until the withdrawal of Sweden). The lack of clear witnesses, no one definitely saw the origin of the shot, established immediate speculation. The input and clean output of the wound, observed in the contemporary stories by Aide-de-Camp André Sicre, suggested a high-speed projectile, but its angle (almost horizontal, from left to right) perplexed from the observers. The enemy lines were 200–300 meters away, a remote possibility for the muskets of the time (precise a ~ 50 meters), but a sniper or a street bullet was not impossible. In a matter of hours, betrayal whispers extended among the troops, since Charles’s aggressive wars had raised enemies even in their intimate circle. A letter from 1718 by General Carl Gustaf Dücker, discovered in Riksarkivet de Stockolm, hinted “unfair hands” among the officers, but no evidence fixed a culprit. The mystery was born, and Sweden cried a king whose death reflected his life: sudden, violent and unforgettable.

2. Theories of the king’s disappearance: accidents or murders?

The debate about the death of Charles XII is divided into two fields: a tragic accident by enemy fire or a murder calculated by his own side. The theory of the street bullet depends on the siege context: Fredriksten’s defenders fired moles and cannons, including grape shots (small iron balls). A 1718 report by Norwegian Captain Peter Tardennskjold, later published inNorway historical magazine, claimed a fortunate shot of a strength gunner, although no specific shooter was identified. The muskets of the time had a limited range, but a Danish shooter with a barrel shot (rare but possible) could have reached 200 meters. The path of the wound supports this: a shot from a higher point of view (strength walls) could explain the almost horizontal path. However, distance and darkness generate doubts, only 2% of the shooting in the 18th century battles gave their mark, according to military historian Lars Ericson Wolke.

The theory of murder, however, has deeper roots. Charles’s relentless campaigns drained the treasure and labor of Sweden, in 1718, the population of the nation had fallen by 10% of the losses of war, byScandinavian Magazine of History. Noble and officers, frustrated by the endless wars and Charles’ negative to negotiate peace (especially with the Peter The Great in Russia), they had a reason. His cousin, Frederick I, who ascended to the throne after death, faced suspicion; An anonymous brochure of 1719 in Stockholm accused him of orchestrating a plot to end the war and take power. The angle of the wound feeds this: a shot from a short distance (within 50 meters) by a Swedish soldier in the trenches is better aligned with the horizontal road than a distant enemy shot. A 1746 Voltaire account, based on Swedish exiles, said a conspirator used a preloaded musket, but no names arose. X Posts Hele is intrigued: “Charles was too stubborn, if his own men took it out!” However, there is no smoking gun (word game), only circumstantial suggestions such as the discontent of the officers and the rapid coronation of Frederick.

3. The autopsy of 1917: a disturbing look at the end of a king

In 1917, almost two centuries later, the Swedish authorities exhumed the preserved remains of Charles XII to resolve the debate. Made in the Riddarholm church, the autopsy focused on its skull, preserved in a lead -lined coffin. The pathologists, led by Dr. Carl Klingberg, documented a 20 mm input wound in the left temple and a slightly larger to the right, consisting of a musket ball or a grape shot (2–3 cm in diameter, byJournal of Forensic Sciences). Photographs, published in 1918Svenska DagbladetThe article revealed a clean and circular wound, without fracturing typical of low -speed impacts, providing a high -speed projectile. The trajectory was almost straight, which implies a short -range shot or a long -distance long distance.

The findings revived the debate. The clean wounds ruled out the shrapnel (which would destroy the fabric) and support the bullet of a sniper or a murderer’s shot. However, the skull did not offer new clues about the identity of the shooter: without waste or integrated fragments. Chemical tests for lead (common in 1718 ammunition) were not conclusive due to coffin pollution. The autopsy, aimed at closing the case, amplified speculation. A 1920Historical magazineThe article pointed out: “The King’s death remains as dark as the night it happened.” Modern forensic reanalysis (for example, a study by the Uppsala 2002 University) are inclined towards the murder due to the accuracy of the wound, but the lack of bullet fragments leaves it unsolved. X Buzz users: “Those photos of 1917 are spooky, definitely a cover -up!”

4. Why the mystery endures: cultural and historical impact

The death of Charles XII is not just a cold case, it is a cultural touch stone. In Sweden, it is a polarizing figure: a hero for the nationalists for his challenge (he won in Narva in 1700 against 4: 1 probabilities) and an imprudent bellicon of critics, who blame him for the decline of Sweden (losing 1/3 of his territory by 1721). His story in the form of death: The Great North War ended with the defeat of Sweden in the Nystad Treaty of 1721, giving the Baltic Domain to Russia. The mystery feeds literature, from 1731 of VoltaireHistory of Charles XIITo modern novels like Ernst Brunner’s 2005Charles King.

The lack of closing drives fascination. Unlike other real murders (for example, Gustav III in 1792, with clear clear), the case of Charles lacks witnesses, physical evidence or confessions. The 1718 battlefield was too chaotic for reliable accounts, and surviving documents (for example, Dücker’s letters) are lazy. Conspiracy theories prosper in this void, some even claim a “Masonic plot” linked to the European powers that fear Charles’s ambitions, although no evidence supports this. Social networks keep him alive: a video of 2023 Tiktok with 1.2m views recreated the siege, which caused 5,000 comments that discuss “Bullet vs. Betrayal”. The 1917 autopsy photos, widely shared in X, add a Macabre Allure. As historian Peter English points out, “Charles’s death is the JFK moment of Sweden, everyone has a theory, nobody has evidence.”

The death of Charles XII in Fredriksten in 1718 remains a riddle wrapped in gunpowder and shadow. Was it a chance of a Norwegian fortress or a plot of cold blood of their own men? The 1917 autopsy, with its chilling photos of the skull, deepened the enigma, demonstrating that only one projectile ended a king’s reign but not who fired it. From the 18th century devoured from Sweden to today’s X debates, this mystery endures, combining forensic puzzles with stories of loyalty and betrayal. What is your opinion: luck or internal work? Leave your thoughts below and keep this case of 300 years alive!