In the turbulent year of 1940, as Europe was engulfed in war and nationalistic fervor, the small German town of Oschatz became the stage for an event that revealed the brutal moral discipline enforced by the Nazi regime.

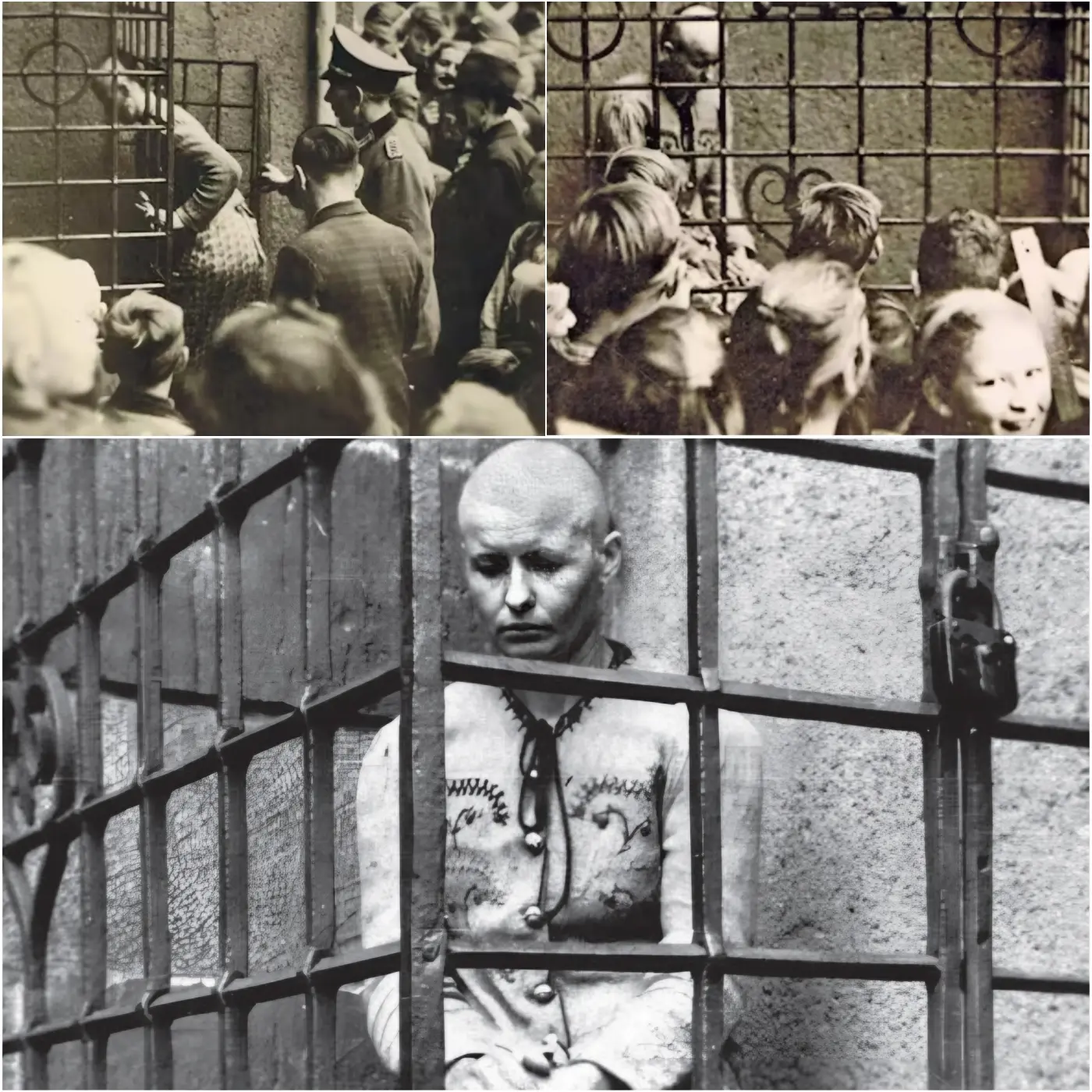

The tragic story of Dora von Nessen, a young woman publicly shamed for her relationship with a Polish prisoner of war, stands today as a reminder of how oppressive ideologies can weaponize intimacy, affection, and personal choice for political control.

According to historical accounts, Dora von Nessen dared to form an emotional connection with a Polish POW stationed nearby. In an era when relationships across national and racial lines were severely punished, her affection was not merely frowned upon—it was declared a crime against the state.

The Nazi authorities condemned her actions as a violation of racial purity laws, and what followed was a shocking display meant to intimidate the entire community as much as to punish her personally.

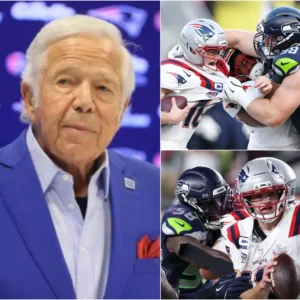

Dora was forced into the town square and displayed before a hostile crowd for nearly four hours. Witnesses described the scene as both chaotic and deeply disturbing.

Some members of the crowd shouted insults, while others stood in horrified silence, unable to reconcile the cruelty unfolding in front of them with the familiar town they knew. Dora bore a sign branding her as “dishonored,” a label used by the regime to strip individuals of dignity and humanity.

The event was not merely a local scandal but part of a broader pattern of public shaming that the Nazi regime employed to enforce social conformity. Relationships between German women and foreign prisoners—especially Slavs, whom Nazi ideology deemed inferior—were treated as threats to national purity.

Dora’s punishment was designed to send a clear message: affection toward the “enemy” was not only forbidden but punishable through humiliation and long-lasting stigma.

What made Dora’s case particularly devastating was her relative isolation. Friends and family members who might have supported her were often too afraid to intervene. The oppressive political climate made compassion risky, and even offering comfort to someone labeled “dishonored” could lead to suspicion or punishment.

In private diaries from the era, residents later reflected on how fear silenced the town, turning ordinary people into passive witnesses of injustice.

The Polish prisoner at the center of Dora’s tragedy remains largely unknown in historical documentation. What is clear, however, is that relationships between POWs and local civilians were far from rare. Many German women formed genuine bonds with prisoners who were assigned to labor in farms, factories, or construction camps.

Historians note that these interactions often exposed the hollowness of Nazi racial ideology, as women saw the humanity of men who had been painted as enemies.

Dora’s punishment was an example of how the regime used women’s bodies as battlegrounds for ideological control. Women were expected to embody racial purity, loyalty, and obedience, and any deviation was met with disproportionate retribution. By publicly humiliating Dora, officials sought to reinforce gender norms, racial boundaries, and community complicity.

The fact that such a severe reaction stemmed from an act of affection highlights how deeply totalitarian systems fear individual agency.

Despite the cruelty of the punishment, Dora’s story also reveals moments of quiet resistance within the community. Some townspeople reportedly looked away in shame, refusing to participate in the spectacle. Others whispered disapproval behind closed doors, though they lacked the power to intervene.

These small gestures, though fragile, remind us that even in repressive environments, the human conscience persists, battling fear and indoctrination.

After the public humiliation, Dora’s life changed irrevocably. She struggled to rebuild a sense of normalcy in a society that had marked her as unworthy. Records suggest that she was monitored by local authorities for months afterward, and employment opportunities were restricted.

The emotional scars were undoubtedly deeper than the social ones, as such punishment sought to break the spirit as much as the reputation.

In modern historical research, Dora von Nessen has become a symbol of those who suffered under the lesser-known social punishments of the Nazi regime. While much of Holocaust history rightly focuses on mass murder and industrial genocide, stories like hers reveal how the regime also attacked everyday expressions of humanity.

Love—simple, private, and deeply personal—could become a political crime under totalitarianism.

Today, historians emphasize the importance of telling Dora’s story not to sensationalize her suffering but to understand the mechanisms of authoritarian control. Public shaming served as a powerful tool to enforce obedience and suppress dissent. By forcing communities to witness degradation, the regime normalized cruelty and discouraged empathy.

Dora’s experience helps modern readers grasp how quickly moral boundaries can erode when a society is governed by fear.

As scholars revisit the past, they highlight the necessity of documenting the lives of individuals who resisted, even unintentionally, by choosing love over ideology. Dora’s forbidden relationship challenges the narrative that citizens uniformly supported the regime’s doctrines.

Her story underscores the truth that human connection persists even in environments designed to suppress it, revealing the enduring power of compassion.

In remembrance, Dora von Nessen’s story serves as a warning against systems that regulate private life and punish emotional autonomy. It encourages readers to recognize the value of individual freedom and the dangers of political ideologies that seek to define the legitimacy of personal relationships.

Her suffering, though rooted in a specific historical moment, resonates across generations as a universal testament to the struggle for dignity.

The events of 1940 in Oschatz remind us that love—in its most innocent and humane form—can become a radical act in times of oppression. Dora’s experience, though tragic, continues to speak to modern audiences about the courage required to remain human in inhuman circumstances.

Her memory stands not as a tale of scandal but as a call to protect the fundamental right to love without fear.