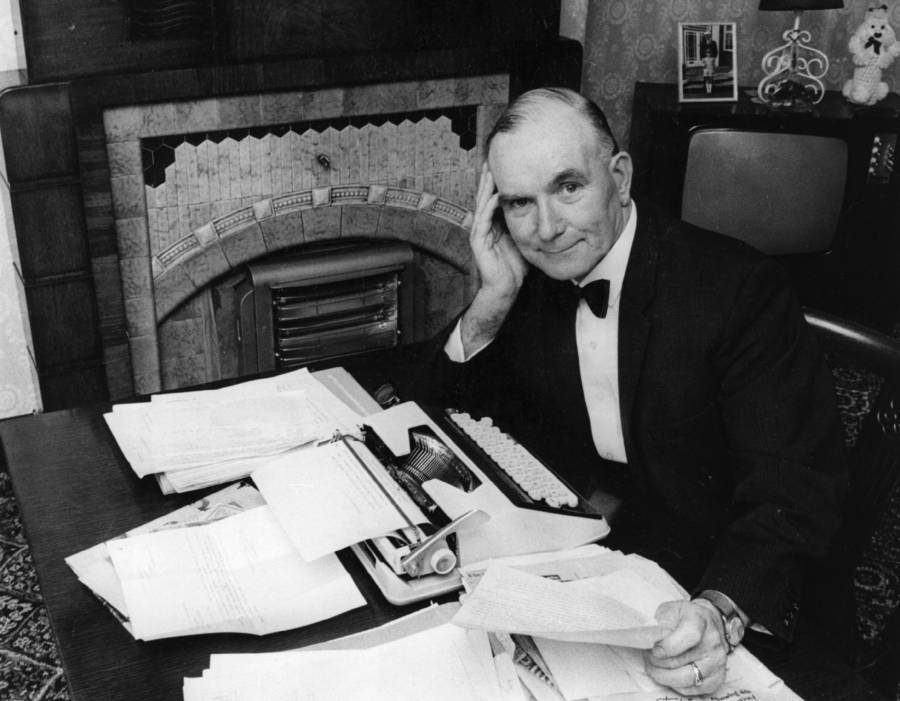

In the 1940s and 1950s, Albert Pierrepoint became one of the most renowned executioners in Great Britain, carrying out the sentences of some of the most notorious criminals of the time, from serial killers to Nazi war criminals. Known for its precision and professionalism, Pierrepoint’s career is a fascinating chapter in modern history, which reflects both the justice system of the time and its personal trip.

A family execution legacy

Born on March 30, 1905 in Yorkshire, Albert Pierrepoint seemed to his unusual profession. With only 11 years, he wrote in a school essay: “When I leave school, I would like to be the official executioner.” This ambition was not born of the mere curiosity: both his father, Henry Pierrepoint, and Uncle, Thomas Pierrepoint, were executioners, which made him a family trade. After the death of his father in 1922, Pierrepoint inherited detailed newspapers and notes about the office of execution, feeding his determination to follow his steps.

Despite his enthusiasm, the opportunities were scarce. Pierrepoint’s initial investigations to the prison commission were rejected due to the lack of vacancies. To stay at Greater Manchester, he assumed several jobs, including delivery work for a shopkeeper. His break came in 1932 when an assistant executioner post was opened. Pierrepoint’s first experience was to observe an execution in Dublin under his uncle’s guidance, marking the beginning of his practical training on a highly specialized role.

Rising to prominence

Pierrepoint’s early race in the 1930s was slow, since the executions were relatively rare in Britain at that time. His first execution as the main pendant came in October 1941, when he made the sentence by Antonio Mancini, a convict gangster. The following year, he executed Gordon Cummins, the infamous “Blackout Ripper”, responsible for a brutal wave of murders in 1942.

World War II drastically expanded Pierrepoint’s role. Between 1945 and 1949, he traveled to Germany and Austria more than 20 times to execute approximately 200 war criminals, including Nazi figures of high profile such as Josef Kramer, known as “The Beast of Belsen” and Irma Grese, a young concentration camp guard. Pierrepoint’s efficiency was remarkable; On February 27, 1948, he carried out 13 executions in a single day, consolidating his reputation as a teacher of his trade.

A public figure and a private fight

Pierrepoint’s work earned him a unique type of fame. After executing numerous Nazi war criminals, he became quasi-heroe in the post-war Britain. With his earnings, he bought a pub called poor fighter near Manchester, where customers went mass to meet the man who had given justice to some of the most vilent figures in history. However, his role was not without personal toll. In 1950, Pierrepoint faced a deeply disturbing momentum when he had the task of executing James Corbitt, a regular in his pub that had committed murder in a jealous anger. The experience joy Pierrepoint, marking the only time he expressed his regret for executing.

Pierrepoint continued his work, executing high profile figures such as John Christie, a notorious serial killer, and Ruth Ellis, whose execution of 1955 for killing her abusive boyfriend caused public protests and fed debates about capital punishment in Britain. The controversy surrounding the case of Ellis highlighted the growing public restlessness with the death penalty, which would eventually lead to his abolition in 1965.

The end of an era

Pierrepoint’s career ended abruptly in January 1956 after a dispute over payment. When an execution was canceled at the last minute, his full rate was not paid, which caused his resignation. By then, he had carried out an estimate of 435 to 550 executions, a number that remains uncertain but underlines his prolific career.

What distinguished Pierrepoint was his meticulous approach. He was known for his quiet behavior and precise calculations to ensure that executions were rapid and human. He carefully adjusted the rope and rope depending on the physicist of a prisoner to achieve a quick break in the neck, avoiding unnecessary suffering. In an interview of the 1960s, he described his process with detachment, emphasizing professionalism: “You should not get involved in any crime they have committed. The person has to die. You must treat them with both respect and dignity as you can.”

A complex legacy

After retiring, Pierrepoint reflected on his career in his 1974 memories,Verdugo: PierRepoint. Surprisingly, he expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of the death penalty, writing: “Executions do not solve anything and are just an outdated relic of a primitive desire for revenge.” However, in an BBC interview with 1976, he suggested that the increase in crime rates could justify the restitution of capital punishment, revealing the complexity of their views.

Pierrepoint lived his last years in silence in Southport, near Liverpool, with his wife. He died on July 10, 1992 at age 87, leaving behind a legacy as the most famous executioner in Great Britain. His life offers a window to a past of justice, where the ability and stoicism of a man shaped the fate of hundreds, from the most despised criminals to those whose sentences caused a national debate.