“They will see my true strength in Tokyo” – Oblique Seville shares how his father instilled inner strength and working with Usain Bolt’s former coach helped him overcome all doubts and make great progress to conquer his own limits every day.

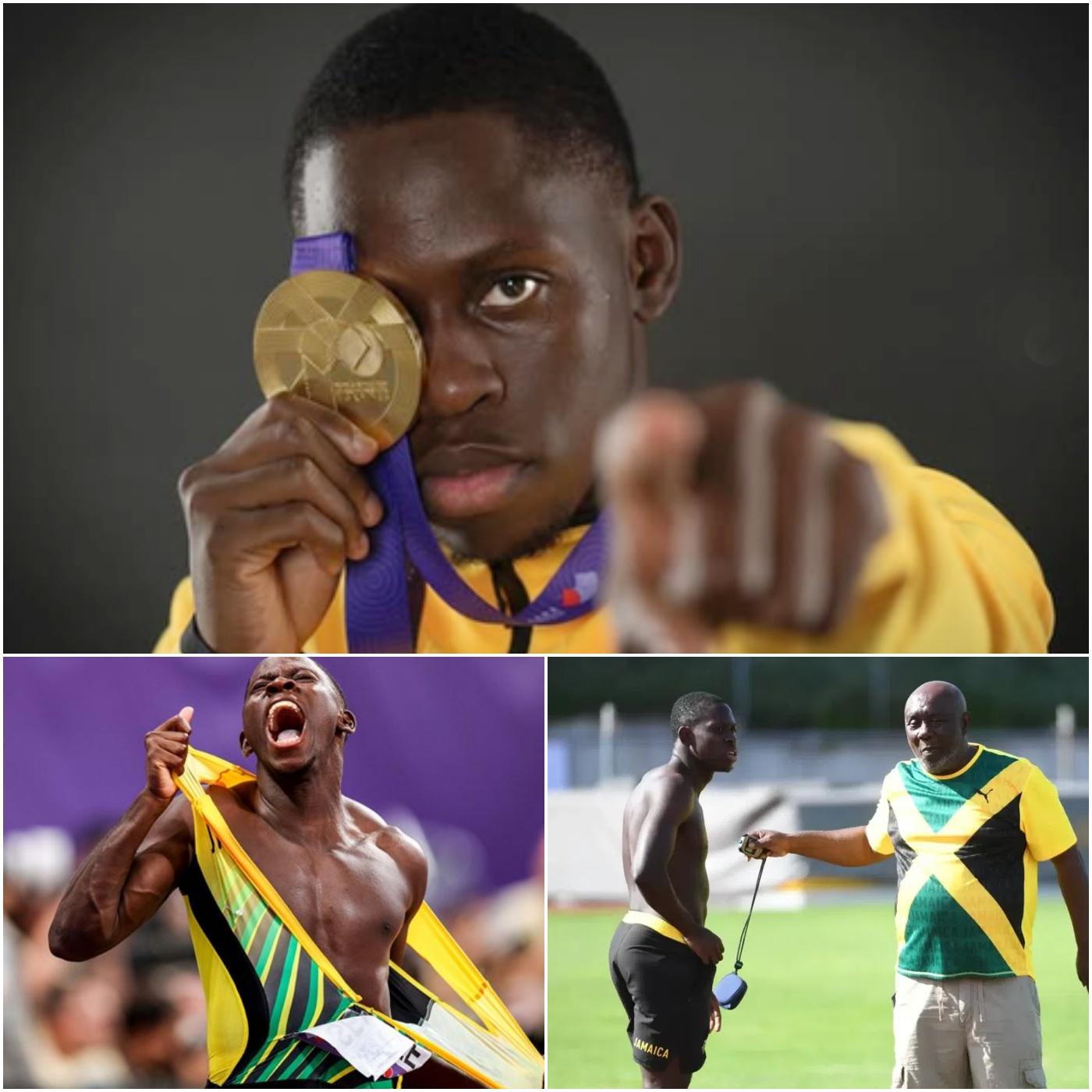

In the sweltering humidity of Tokyo’s National Stadium on September 14, 2025, Oblique Seville did more than just win a race. The 24-year-old Jamaican sprinter exploded off the blocks, his long strides eating up the track with a ferocity that silenced doubters and reignited Jamaica’s sprinting legacy. Clocking a blistering personal best of 9.77 seconds, Seville surged past teammate Kishane Thompson in the final meters to claim the men’s 100m gold at the World Athletics Championships. It was Jamaica’s first global 100m title in nine years, since Usain Bolt’s last hurrah in 2016, and Bolt himself was there, leaping from his seat in the stands, fists pumping like a man reliving his own glory days.

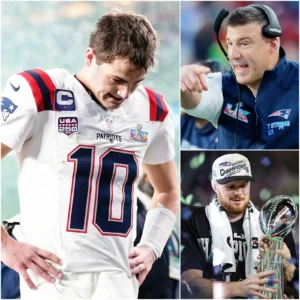

For Seville, the victory was the culmination of a journey marked by heartbreak, resilience, and an unyielding drive to prove himself. “They will see my true strength in Tokyo,” he had declared in the weeks leading up to the championships, a quiet vow born from years of near-misses and personal loss. As the crowd’s roar washed over him, vest torn in ecstatic celebration, Seville’s eyes welled with tears—not just for the medal, but for the father who had planted the seeds of that inner fire long before the world took notice.

Born in 2001 in the rural community of Ness Castle, Jamaica, Oblique grew up in a home where dreams were as abundant as the island’s sunshine. His father, Gerald Seville, was a cricket enthusiast with a gentle spirit and an unshakeable belief in his son’s potential. Gerald wasn’t a track coach; he was a man who worked odd jobs to keep the family afloat, but he saw something in little Oblique—a spark of speed during impromptu races in the churchyard or along dusty backroads. “He always told me, ‘Son, strength isn’t just in your legs; it’s in here,'” Seville recalls, tapping his chest during a recent interview upon his return to Kingston. That “here” was the heart, the mind, the quiet resolve to rise above hardship.

Gerald’s lessons came in simple, profound moments. When Oblique was just seven, his father gifted him a small camera, sparking a lifelong love for capturing life’s fleeting images. “I love pictures,” Seville says with a soft smile, flipping over his phone case to reveal a faded 2001 snapshot of Gerald cradling a wide-eyed infant—himself. It was more than a hobby; it was a way to freeze time, to hold onto joy amid struggle. But in late 2018, when Oblique was 17 and on the cusp of his athletic breakthrough, Gerald died suddenly from a suspected heart attack. The loss shattered the family. “I was extremely broken,” Seville admits. “Dad was my rock. He believed I could be great before I even believed it myself.”

Grief could have derailed him. Instead, it forged him. At Calabar High School, a breeding ground for Jamaican sprint stars, Oblique had dabbled in cricket and football, even swimming in local rivers. But track called loudest, echoing the legends he’d grown up idolizing—men like Asafa Powell and, above all, Usain Bolt. Bolt’s larger-than-life presence loomed large; as a boy, Seville devoured footage of the Lightning Bolt’s world-record runs, dreaming of one day sharing the same lane. “We all watched Usain as kids,” he says. “His background was like mine—humble, hungry. I wanted that.”

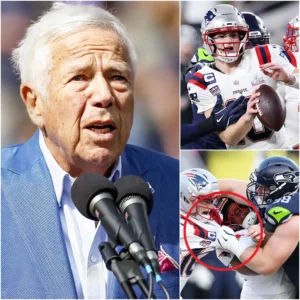

The turning point came at age 10, when Oblique boldly told his mother he wanted to train under Glen Mills, Bolt’s legendary coach. It wasn’t a whim; it was destiny calling. Mills, the architect behind Bolt’s eight Olympic golds and multiple world records, had founded the Racers Track Club in Kingston, a mecca for aspiring sprinters. By 2019, after impressing at junior meets, Seville joined the club, stepping into shoes once worn by the greatest of them all. “When I first met Coach Mills, I was nervous,” Seville shares. “But he saw me—really saw me. He said, ‘You’ve got Bolt’s drive, but you need to find your own rhythm.'”

Under Mills’ tutelage, Seville’s transformation was methodical, almost surgical. The coach, now in his 80s but as sharp as ever, emphasized not just speed but sustainability. “Glen is like a father to us,” Seville says, his voice thick with gratitude. “He taught me to conquer doubts one stride at a time. With Bolt, he built an empire; with me, he’s rebuilding one.” Mills’ philosophy—patience, precision, mental fortitude—resonated deeply. Early sessions focused on biomechanics: refining Oblique’s explosive start, which had faltered in his youth, and honing his powerful drive phase. “I had the legs, but not the belief,” Seville explains. “Coach broke it down: visualize the pain, embrace it, turn it into power.”

Doubts lingered, though. At the 2024 Paris Olympics, Seville finished fourth in the 100m semis, agonizingly close to the final. Injuries nagged—a hamstring tweak here, a nagging toe issue there—and whispers grew: Was he Jamaica’s next big thing, or just another promising talent? Noah Lyles, the brash American Olympic champion, added fuel with pre-Tokyo mind games, touting his own invincibility. Seville, ever stoic, brushed it off: “Trust in God. Words don’t win races; work does.”

Bolt, too, became a pillar. Since Gerald’s passing, the sprint king has stepped in as mentor and motivator, dropping by Racers for casual chats and sage advice. “Usain told me family is everything,” Seville says. “He lost his way sometimes, but family brought him back. Now, he’s mine.” Bolt’s endorsement carried weight; earlier in 2025, he publicly backed Seville to challenge his 9.58-second world record, saying, “Oblique has it—the hunger, the heart.”

The progress in 2025 was undeniable. Seville opened the season with a bang, running 9.97 at the Racers Grand Prix in June, upsetting Lyles in front of a home crowd. He followed with a rain-soaked 9.87 win at Athletissima in Lausanne, then a 9.86 victory at the London Diamond League, again besting Lyles and Botswana’s Letsile Tebogo. At the Jamaican Championships, he nabbed silver behind Thompson in 9.83, earning his Worlds spot. Each race chipped away at his limits, Mills tweaking drills to build endurance and explosiveness. “Every day, we conquer something new,” Seville notes. “Coach pushes you to 110%, then teaches you that’s just the start.”

Tokyo was the proving ground. In the final, Thompson bolted to an early lead, Lyles lurked menacingly, but Seville stayed composed, channeling Gerald’s voice: “Strength from within.” He pounced in the last 20 meters, his form impeccable, crossing first by a razor-thin 0.005 seconds over Thompson, with Lyles bronze. “Great—that’s the only word,” Seville gasped post-race, gold around his neck. “Thanks to God, to Coach, to Dad.”

Back in Jamaica on September 24, Seville returned to a hero’s welcome—modest by Bolt-era standards, but heartfelt. Fans mobbed him at Norman Manley International Airport, chanting “Golden Boy!” He urged more respect for his name, then turned philosophical: “This isn’t the end; it’s the beginning.” Even a recent toe procedure—removing nails from both big toes, sidelining him for a month—can’t dim his fire. “Recovery is just another limit to conquer,” he says.

Seville’s story signals a renaissance for Jamaican sprinting. With Thompson’s silver and Bolt’s shadow fading into mentorship, a new guard rises. He dreams big: sub-9.70 times, Olympic gold in 2028, maybe even Bolt’s record. “The current crop? We’re getting to 9.6 soon,” he predicts. “But Bolt’s the best—always.” For now, Oblique Seville stands tall, a testament to inner strength passed from father to son, refined by a master’s hand. In Tokyo, the world saw his true power. Tomorrow, they’ll see more.